By Elizabeth Preston, AuD, CCC-A

Background

The importance of consistent wear time has been drilled into me as a pediatric audiologist and it is important to have conversations with families about this regularly. Conversations around wear time are easier if the stage is set early. The sooner we stress the importance of device use and the impact it has on language outcomes for the child, the better.1-3 We use a co-treat model in our clinic, so a speech language pathologist (SLP) who is LSL certified is always seeing the family on the same day as the audiology appointments for young children especially during the first year after cochlear implantation. There are many advantages to having this model; one of those advantages is having both the audiologist and SLP discussing device use and stressing the importance of wear time.

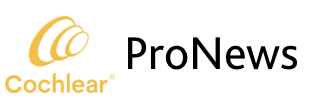

I was also always using the “10 hours a day” (children wear their device at least 10 hours per day) reference for getting a full day of use in. In our clinic, we now use “80% of the day” to take into consideration increase in awake time as a child gets older.4 A child quickly outgrows being awake 10-12 hours a day. To help providers start the conversation about wear time and its importance, we have posted the below figure in each treatment room. We feel it is an easy visual for families to read and understand and we are often asked about it.

Case study

I’d like to share the story of Gwen (name has been changed) to give an example of how taking the time to have hard conversations around wear time helped her outcomes in the long run. Gwen had an uneventful pregnancy/birth and she passed her newborn hearing screening in both ears. However, her parents were concerned by two months of age about her lack of responses to sound, so they asked their pediatrician for a referral for a diagnostic auditory brainstem response (ABR). Due to COVID, that testing was a bit delayed. A no-response ABR was obtained in both ears at 6 months of age and hearing aids were fit by seven months of age. There is a positive family history of hearing loss as her father has been diagnosed with Waardenburg Syndrome.

Gwen was referred for a cochlear implant (CI) evaluation and later she was bilaterally implanted. Gwen struggled to maintain consistent wear time from the very beginning. We had several conversations discussing strategies the family could use, discussing daily routines and where the family could improve upon their efforts. We also discussed different retention options to help keep the processors on. They tried wearing the Kanso® 2 Sound Processors and utilizing the HugFits™. To complicate our efforts, the family was also getting advice from a family member who is Deaf and encouraging them to focus more on sign language than on consistent device use . Our message remained consistent: If Gwen is going to talk, she needs to wear her devices consistently and be spoken to. We encouraged the family that they could choose to teach sign language along with spoken language if they wanted her to learn both languages.

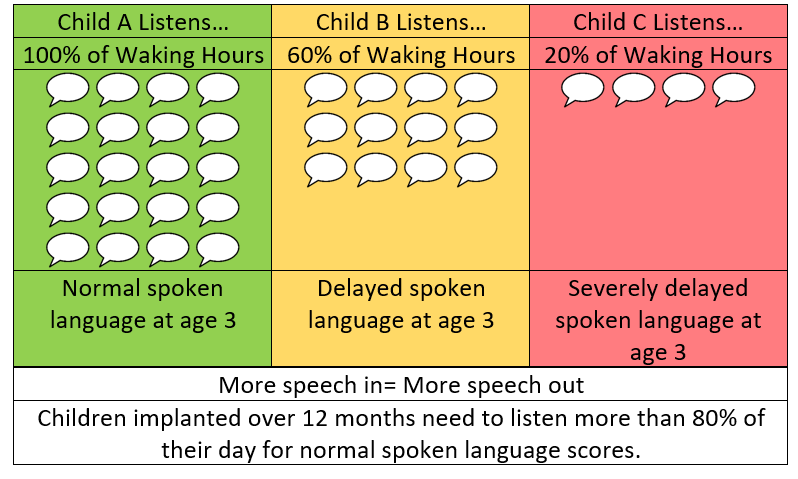

Data also helped inform our counseling strategy. At initial activation, wear time started at 40-50% of her waking hours. Unfortunately, it reduced to 10% after three months of device use, which also meant she was not making much progress with her listening and her speech. Her parents were not seeing the benefit of keeping them on.

After many discussions with the family to find a solution that would work for them to keep the devices on, Gwen’s wear time has improved. This was a team effort including the parents, audiologist, speech language pathologist and early interventionist. She has begun to make great progress with her spoken language as well as learning a few signs and her parents are now seeing the benefits of having the devices on. There is still work to do; however, Gwen is on the right trajectory and we will continue to support her and her parents through this journey.

Results

By taking time to work as a team and talk through different strategies to address the struggles and celebrate the successes, Gwen’s wear time improved and she began to make quick progress with her listening and spoken language. These conversations were often hard and we didn’t always feel equipped to answer all the questions, but we did not shy away and we believe this is what has made the difference.

Helpful takeaways:

- Start the wear time conversation at the very beginning of discussions about the cochlear implant

- Discuss retention options early to have a plan and possibly start practicing that plan prior to surgery (e.g., wearing a headband to get used to having it on prior to activation)

- Celebrate the small successes

- Make sure everyone on the team is using the same messaging and working together

- Keep the conversations focused on the family coming up with strategies if possible (prompting may be necessary to start ideas flowing)

- Review datalogging so that timely conversations can happen with family and between appointments if needed

- Keep conversations as positive as possible and validate the family’s feelings

No matter how young infants are when implanted, they will not close the gap with their normal hearing peers without wearing their devices 80% or more of their awake time. If we meet the family where they are and offer our support, their child will be more likely to succeed.

To hear more from Dr. Preston, listen to her pediatric-focused AudiologyOnline course.

About the author: Dr. Elizabeth Preston just finished up as Pediatric Cochlear Implant Audiologist, Audiology Clinic Manager and Clinical Assistant Professor at The Children’s Cochlear Implant Center at UNC. She earned her degrees from Texas Tech Health Sciences Center and has over 16 years of clinical experience. Her career as an audiologist has focused on working with children who are deaf or hard of hearing gain access to spoken language through listening. She began her career as a diagnostic audiologist, fitting hearing devices for children with varying degrees of hearing loss. As the Audiology Clinic Manager with UNC’s Cochlear Implant Team, she helped children in her region gain access to cochlear implants and receives high-quality follow-up services. This included participating in clinical research and working to broaden the number of children who have access to services. Dr. Preston also provides training to professionals and graduate students throughout the United States to improve the diagnosis and treatment of children who are deaf or hard of hearing.

References

- Gagnon EB, Eskridge H, Brown KD. (2020, March)Pediatric cochlear implant wear time and early language development. Cochlear Implants Int. 21(2):92-97. doi: 10.1080/14670100.2019.1670487. Epub 2019 Sep 29. PMID: 31566100.

- Gagnon EB, Eskridge H, Brown KD, Park LR. (2021, April). The impact of cumulative cochlear implant wear time on spoken language outcomes at age 3 Years. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 64(4):1369-1375. doi: 10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00567. Epub 2021 Mar 30. PMID: 33784469.

- Wiseman KB, Warner-Czyz AD, Kwon S, Fiorentino K, Sweeney M. (2021, Jul-Aug). Relationships between daily device use and early communication outcomes in young children with cochlear Implants. Ear Hear. 42(4):1042-1053. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000999. PMID: 33974791.

- Jenco, Melissa. (2016, June). AAP endorses new recommendations on sleep times. The official Newsmagazine of the American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aappublications.org/news/aapnewsmag/2016/06/13/Sleep061316.full.pdf

In the United States, the Cochlear Nucleus Implant System is approved for use in children 9 to 24 months of age who have profound sensorineural hearing loss in both ears and demonstrate limited benefit from appropriate hearing aids. Children 2 years of age or older may demonstrate severe to profound hearing loss in both ears.

In the Canada, the Cochlear Nucleus Implant System (CI500 and CI600 Series) is approved for use in children 9 to 24 months of age who have profound sensorineural hearing loss in both ears and demonstrate limited benefit from appropriate hearing aids. Children 2 years of age or older may demonstrate severe to profound hearing loss in both ears.